In the heart of Dearborn, Michigan, lies a hidden gem of American history and an architectural marvel—the Ford Homes Historic District. The district is celebrated for its distinct array of homes crafted by the Ford Motor Company in the 1910s and 1920s, specifically for its employees. These are more than just a collection of houses; they represent a bold experiment in urban planning, architecture, and social welfare. Born out of Henry Ford's visionary approach to worker welfare and efficiency, these homes were designed to offer a slice of the American dream: affordable, quality housing within a nurturing community.

Addressing a Housing Crisis with Innovative Solutions

The initiative to create a residential community in Dearborn, a suburb just outside of Detroit where Ford had opened a new tractor manufacturing plant, was driven by a clear need. The plant's workforce, primarily hailing from Detroit, contended with a significant housing crisis and soaring living costs in the city, which forced them into lengthy daily commutes by trolley. This situation was further aggravated by a spike in real estate speculation following World War I, leading to skyrocketing housing prices. Seizing the opportunity to provide affordable, high-quality housing that would be within reach of middle-class and aspirational working-class families, Ford took decisive action.

Constructing a Community: The Ford Approach

The Dearborn Realty and Construction Company, a subsidiary of the Ford Motor Company led by a board including Clara Ford, E.G. Liebold, and the young Edsel Ford, aimed to tackle housing issues head-on. Through this subsidiary, Ford was able to directly influence the creation of communities around its manufacturing plants, providing affordable housing options for its employees and supporting the company's broader goals of improving worker welfare and fostering a loyal workforce. The company acquired a nine-acre plot, bordered to the north by the Michigan Central Railroad tracks near the tractor factory, and began developing an innovative subdivision.

Revolutionary Construction Techniques and Design

Construction kicked off in 1919 and extended into 1920, employing a workforce of 250 to 500 individuals from Ford's factories. The construction process mirrored an assembly line, with each crew and worker assigned specific duties. All necessary tools and materials were readily available, supplied by on-site facilities such as a planing mill, lumber warehouse, plumbing and tin shop, or directly via freight cars.

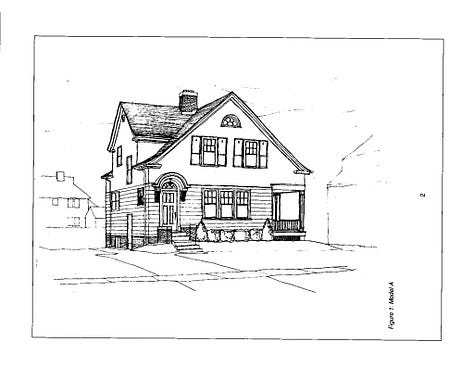

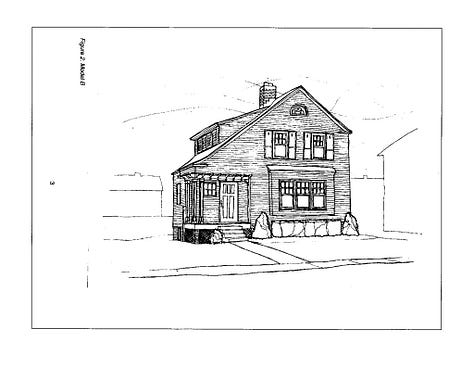

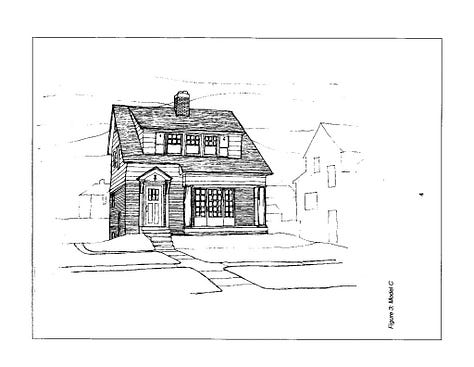

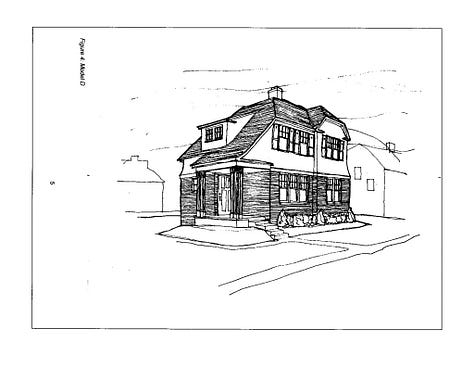

The lead architect, Albert G. Wood, developed designs for six unique house types, starting with Model A and concluding with Model F. Most of these homes featured three bedrooms, while a select few offered four. Each home was constructed with two stories, featured a central chimney, and shared a uniformly block-like architecture. However, through clever adjustments to construction details and altering the positioning of each structure, Wood successfully gave the impression of a diverse range of designs.

A Focus on Community and Modern Amenities

The most noticeable variations lie in the assortment of roof shapes—hip, gable, gambrel, jerkin-head—each artfully arranged in different alignments. At times, gables face the street directly; other times, the rooflines run parallel, altering how porches, entryways, and windows interact with each other and the street. Often, triple sets of double-hung windows, characteristic of the post-World War I period, are positioned on the fronts or sides of the homes, enriching the visual appeal and hinting at the layout of living or dining areas.

The choice of building materials was equally intentional, with various combinations to achieve distinct appearances. Exterior wall materials ranged from broad and narrow clapboards, cedar shingles, brick, stone, and stucco, used alone or together.

Despite a steadfast commitment to quality craftsmanship, the economic downturn during the building phase necessitated some material substitutions. Oak floors and cabinets, featured in the initial homes, were later substituted with more economical woods such as fir.

Like the houses, the plots were designed to be cozy but not excessively spacious. They featured front and back yards, providing space for modest gardens, trees, bushes, and decorative plants. The implementation of underground wiring and electric poles placed in the 20-foot-wide lanes behind the properties enabled access to modern amenities. Interestingly, for a development linked to America's leading car manufacturer, garages were not included as standard but were an optional extra, likely as a measure to keep costs down (a reflection of Ford's well-known practicality). Only a handful of garages were constructed, typically at the back of the lot, as was customary at the time.

Ensuring Accessibility and Fostering a Sense of Belonging

Ford made the subdivision accessible to all and not just limited to his employees (many would have found the $5,750 to $9,750 price range out of reach). Buyers were required to fulfill specific standards: Ford sought stability and "suitability" in all potential homeowners. To curb real estate speculation, new owners had to commit not to sell their property for five years, with the Dearborn Realty Company retaining the option to repurchase any home within that period should the owner exhibit moral or financial unreliability.

Each home was designed with the welfare of its occupants in mind. The interiors of the homes were designed to maximize space and functionality. They featured efficient floor plans that accommodated the needs of working families, with separate living and dining areas, kitchens, and multiple bedrooms. A solitary bathroom was strategically placed on the upper floor, easily accessible from the bedrooms. Despite being built in the 1910s and 1920s, the homes were equipped with modern conveniences such as indoor plumbing, central heating, electrical lighting, and electrical ranges in the kitchen. These features were not universally standard at the time and represented a significant improvement in living conditions for the workers.

Modern Innovations and Community Planning

Ford's project revolutionized housing development in the early 20th century, setting a precedent for modern construction and urban planning. Adopting prefabricated construction achieved unprecedented efficiency and cost savings, laying the groundwork for methods now central to the industry. The project's modular housing designs brought flexibility and cost-effectiveness to urban development, enabling diverse architectural styles without sacrificing simplicity. Moreover, its emphasis on optimizing home space and functionality has become a cornerstone of urban design, especially vital in densely populated cities where space efficiency is paramount.

The neighborhood was designed with integrated communal spaces, fostering a strong sense of community and belonging. Its pedestrian-friendly layout prioritized walkability and safety, principles now central to modern urban planning to enhance livability and reduce vehicle reliance. The inclusion of diverse housing options promoted social inclusion, influencing current strategies to create communities that support mixed-income residents. This has guided the development of current social housing policies and participatory planning processes, ensuring that urban development projects meet the needs and interests of the community at large.

Preserving History and Fostering Community Spirit

The neighborhood was officially recognized as a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places on December 29, 1998. This designation was granted to acknowledge the area's significance in architecture, community planning, and development and its role in social history, particularly in relation to its origins with the Ford Motor Company and its efforts to provide housing for its workers in the early 20th century. Being listed on the National Register of Historic Places helps protect the district and acknowledges its importance to the historical and cultural fabric of the United States.

Today, the Ford Homes Historic District retains its charm and community spirit. While the residents may no longer be predominantly Ford employees, the legacy of innovation, community, and quality of life endures. The neighborhood has adapted to the modern era, embracing diversity and new technologies yet meticulously preserving its historical essence. Annual events, community gatherings, and a shared commitment to preservation foster a strong sense of identity among residents.

The transition from a company town to a historic district has not been without challenges. Issues of preservation versus modernization, maintaining affordable housing, and ensuring the district remains a living community rather than a museum piece have been at the forefront of community discussions. Yet, the Ford Homes Historic District stands as a model of sustainable community development, demonstrating that historical preservation and modern living can coexist harmoniously.