How Saving Grand Central Station Redefined Historic Preservation

The Landmark Case That Anchored a Movement and Protected Our Past

My daughter Elizabeth just returned from a class trip to New York City. While she was there, she got to see Grand Central Station. She excitedly told me about how its beauty and atmosphere struck her.

I remembered the landmark case at the heart of saving the station from demolition and thought I would share the story with you. In this post we'll explore the critical legal battle that went to the Supreme Court to save this landmark, setting a precedent for historic preservation across the United States. This wasn't just about keeping an old building standing; it was a fight to recognize the value of our architectural and cultural heritage, impacting how historic sites are preserved today.

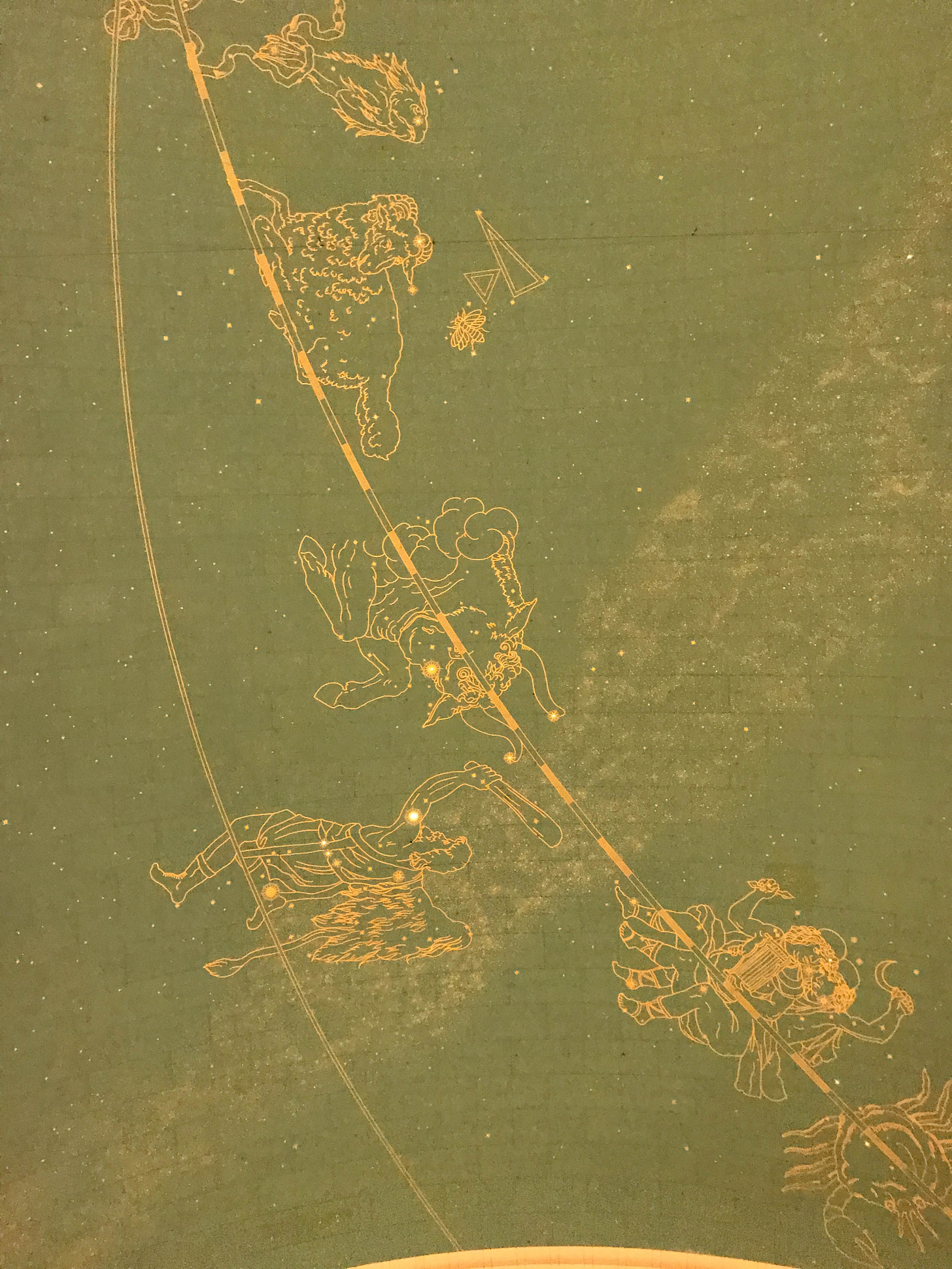

Grand Central Station is more than just a train station in the heart of New York City; it's a landmark that holds a special place in the hearts of New Yorkers and travelers alike. It inspires a blend of awe and a profound sense of connection. When you step into its grand space, there's an immediate sense of being part of something larger than yourself. It's not just the physical vastness of the place that impresses; it's the realization that you're standing in a historical site that has been a crossroads for millions of people over the years. This connection to history, combined with the station's stunning features—the celestial ceiling with painted constellations, the grand staircases, the opulent chandeliers, the iconic four-faced clock, and the lively energy of travelers coming and going, creates a feeling of wonder and belonging.

Grand Central Station, officially known as Grand Central Terminal, has a rich history rooted in the evolution of New York City's transportation needs and architectural innovation. Its story begins in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, reflecting the era's industrial growth and the increasing importance of rail travel.

1871 - Grand Central Depot: The story begins with the Grand Central Depot, which opened in 1871. This facility was built by Cornelius Vanderbilt, who consolidated three separate railroad terminals into one. The original structure featured a large train shed with tracks for the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad, the Harlem River Railroad, and the New Haven Railroad. Despite its size and ambition, the depot soon struggled to handle the increasing volume of rail traffic.

1899-1900 - Grand Central Station: To address its limitations, the depot underwent a major renovation between 1899 and 1900, transforming into Grand Central Station. This renovation included the addition of new platforms, tracks, and a new facade. However, this expansion was still insufficient to cope with the increasing demands placed on the station, especially with the advent of longer trains and more frequent service.

The Early 20th Century - Plans for a New Terminal: The early 20th century brought a pivotal moment for Grand Central. The station was operating at full capacity, and its at-grade rail lines were causing congestion and accidents on the streets of New York. The tragic Park Avenue Tunnel crash of 1902, which resulted in 17 deaths, underscored the urgent need for a safer, more efficient transportation solution. This tragedy spurred action for comprehensive changes.

1903-1913 - Grand Central Terminal: The decision to completely overhaul and rebuild the station led to the creation of Grand Central Terminal. This ambitious project expanded capacity and reimagined the entire Manhattan rail system. The plan, initiated by William J. Wilgus, the chief engineer of the New York Central Railroad, included electrifying the railroads and burying the tracks underground, eliminating the dangerous street-level crossings. This electrification allowed trains to run into an underground terminal, facilitating the development of the area above the tracks.

The construction of the new terminal began in 1903. It was a monumental engineering feat involving demolishing the existing station and excavating land without disrupting the ongoing train services. The new terminal opened on February 2, 1913, heralded as a marvel of engineering and architecture. It featured grandiose spaces such as the Main Concourse with its iconic celestial ceiling, vast waiting rooms, and an intricate network of tracks and platforms designed to handle the flow of passengers efficiently.

Peak of Rail Travel: In the years following its opening, Grand Central Terminal thrived as a critical node in the nation's rail network. The terminal's innovative design allowed it to handle a vast number of trains and passengers efficiently. During this era, rail travel was Americans' primary long-distance transportation mode. Grand Central served as the starting point or destination for millions of journeys.

Architectural and Cultural Icon: Grand Central's architectural grandeur and innovative design made it an immediate cultural icon. Its Beaux-Arts facade, spacious Main Concourse with the celestial mural, elaborate staircases, and the famous four-faced clock became symbols of New York City's ambition and elegance. The terminal was more than a transportation hub; it was a public space where people from all walks of life could marvel at human ingenuity and artistry.

Impact of the World Wars: During both World Wars, Grand Central played a significant role in the American war effort as a transit point for troops moving across the country. The terminal saw heightened activity, with soldiers and military personnel frequently among its passengers. This period underscored the strategic importance of rail transportation and Grand Central's role in national defense and mobilization.

The Great Depression: The economic downturn of the 1930s affected all sectors of American life, including railroads. While Grand Central Terminal remained a vital transportation hub, the railroads faced financial difficulties due to decreased passenger numbers and competition from emerging modes of transportation such as automobiles and buses. Despite these challenges, Grand Central continued to serve as a vital artery in New York City's transport system.

Innovations and Adaptations: Throughout this period, Grand Central saw various innovations and adaptations to meet changing transportation needs and technologies. This included the introduction of new services, the upgrading of facilities, and efforts to maintain the terminal's relevance and efficiency as a transportation hub.

The Beginning of Decline: By the late 1940s and early 1950s, the signs of decline in passenger rail travel were becoming evident. The post-World War II era saw a boom in automobile ownership, the expansion of the interstate highway system, and significant advancements in aviation. These developments began to encroach on the dominance of rail travel, setting the stage for Grand Central's challenges in the subsequent decades.

This decline affected the revenues of the New York Central Railroad (later part of the Penn Central Railroad after a merger), the owner of Grand Central Terminal. The decrease in rail traffic made the vast, centrally located terminal increasingly seen as an underutilized asset in a prime real estate market.

Real Estate Pressures: The location of Grand Central Terminal in Midtown Manhattan, one of the world's most valuable real estate markets, made the site attractive for developers. The economic logic of the time suggested that the land could be more profitably used for other purposes, such as office buildings or retail spaces, rather than a train station that was perceived to be past its prime.

Financial Difficulties of the Railroad Companies: By the 1960s, the Penn Central Railroad faced severe economic difficulties. To stabilize its finances, the company sought to leverage the valuable real estate on which Grand Central Terminal stood. This led to proposals to demolish or drastically alter the terminal to make way for commercial developments that could generate more revenue than the station was producing.

Proposed Developments: One of the most controversial proposals came in the late 1960s when Penn Central Railroad announced plans to construct a skyscraper above Grand Central Terminal. The design, proposed by architect Marcel Breuer, involved building a tower over the terminal's Main Concourse. It would have required significant structural alterations, effectively destroying much of its historic and architectural integrity.

However, New York City had designated Grand Central Terminal as a historic landmark, protecting its exterior and interior under the city's Landmarks Preservation Law, enacted in 1965. When the city's Landmarks Preservation Commission denied Penn Central's proposal to construct the tower, Penn Central sued the city. In Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City, they claimed that the landmark designation infringed upon their rights under the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, labeling it a "taking" because it significantly limited their ability to profit from their property.

Legal Proceedings: As the legal battle escalated to the Supreme Court, Penn Central contended that the landmark law's restrictions constituted an unjust taking requiring compensation. Conversely, the City of New York defended the landmark designation as a legitimate exercise of its police powers to preserve the public's interest in historical and cultural heritage. It argued that the landmark law still allowed Penn Central to use the property economically.

Supreme Court Decision: In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court upheld the New York City Landmarks Preservation Law, ruling that it did not constitute an unconstitutional taking of Penn Central's property. The Court's opinion, delivered by Justice William J. Brennan, Jr., introduced what came to be known as the "Penn Central Test" for determining when a regulatory action constitutes a taking that requires compensation. The test considers several factors, including the economic impact of the regulation on the claimant, the extent to which the regulation has interfered with distinct investment-backed expectations, and the character of the governmental action.

The Court found that New York City's landmark law was designed to preserve structures with special historical, cultural, or architectural significance and that this was a legitimate public purpose. It also noted that Penn Central could still use the terminal for its intended purpose as a railroad station and could potentially develop the airspace above it in other ways that complied with the landmark designation. Thus, the restrictions imposed by the landmark designation were deemed not to constitute a taking requiring compensation.

Preservationists and Advocacy Groups: While not directly involved in the legal proceedings, various preservationist groups and public figures supported the efforts to save Grand Central Terminal and influenced public opinion and policy regarding historic preservation. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis played a pivotal role by leveraging her stature as a former First Lady and a respected societal figure and her passion for historic preservation to rally support against the proposed alterations and potential demolition of the iconic landmark.

· Letter-Writing Campaign: Onassis penned letters to city officials, including the mayor, urging them to take action to protect the terminal. One of her most quoted lines from this campaign is a letter to Mayor Abraham Beame, in which she wrote, "Is it not cruel to let our city die by degrees, stripped of all her proud monuments until there will be nothing left of all her history and beauty to inspire our children?"

· Testifying: She participated in public hearings and testified on the importance of preserving Grand Central, articulating the potential loss to future generations if such historical structures were allowed to be demolished or significantly altered.

· Press Conferences: Onassis held press conferences and participated in interviews, using her influence to draw media attention to the preservation efforts. Her involvement was pivotal in mobilizing public opinion and generating broader media coverage, putting pressure on decision-makers.

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis's advocacy was a key factor in the successful campaign to preserve Grand Central Terminal. Her actions exemplified how influential individuals can contribute to public causes and mobilize support for preservation efforts. Her involvement highlighted the broader cultural and historical implications of the preservation debate, contributing to the eventual victory in the Supreme Court case and setting a precedent for preserving other historic sites across the United States.

Impact and Legacy: The decision in Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City profoundly impacted historic preservation efforts across the United States. It affirmed the power of local governments to protect historic landmarks. It established a legal framework for balancing private property rights with the public interest in preservation. The case has been cited in numerous subsequent legal decisions on land use, zoning, and historic preservation, making it a seminal case in American urban planning and property law.

After the Supreme Court ruling, Grand Central Terminal entered a period of renewal and revitalization that would restore its former glory and adapt it for contemporary use. The efforts to renovate and repurpose Grand Central were multifaceted, aiming to preserve its historic architecture and improve its functionality as a transportation hub and public space. These renovation efforts were critical in transforming Grand Central from a deteriorating landmark into a vibrant, bustling center of urban life.

Comprehensive Renovation in the 1990s:

Major Restoration Project: The most significant renovation of Grand Central Terminal began in the mid-1990s and was completed in 1998. This extensive project was spearheaded by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) and aimed to meticulously restore the terminal's architectural details while modernizing its facilities for the 21st century.

Architectural Restoration: Key elements of the restoration included cleaning the vast celestial mural on the ceiling of the Main Concourse, revealing a sky obscured by decades of grime and cigarette smoke. The marble surfaces, staircases, and chandeliers were restored to their original condition, and the terminal's grand windows were uncovered and cleaned to allow natural light to flood the interior spaces again.

Infrastructure and Amenities Upgrades: Beyond cosmetic restoration, the project also included significant infrastructure upgrades. This involved improving the terminal's electrical, mechanical, and plumbing systems, enhancing safety and accessibility features, and upgrading retail and dining spaces to cater to the needs of commuters and visitors.

Retail and Dining Revival: The renovation transformed Grand Central into a retail and dining destination, with the introduction of the Grand Central Market, a food hall offering a variety of gourmet foods, and the Dining Concourse, featuring a range of eateries. High-end shops and pop-up stores also found a home in the terminal, turning it into a shopping destination.

Adaptive Reuse and Public Space Enhancement:

Event Space: Grand Central's Vanderbilt Hall, once a waiting room, was repurposed as a premier event space, hosting exhibitions, markets, and private events. This adaptive reuse strategy contributed to the terminal's financial sustainability and cultural vibrancy.

Public Spaces: The renovation efforts prioritized enhancing public spaces within the terminal. The Main Concourse continued to serve as a grand public room for New York City. People could meet, admire the architecture, and participate in public events there.

Impact on Urban Fabric:

Economic and Cultural Revitalization: The successful renovation of Grand Central Terminal spurred economic growth and cultural revitalization in the surrounding Midtown Manhattan area. It attracted new businesses, tourists, and real estate development, contributing to the vibrancy and resilience of New York City's urban core.

Preservation as a Model: The transformation of Grand Central became a model for the preservation and adaptive reuse of historic structures worldwide. It demonstrated how such projects could respect and preserve historical integrity while meeting modern needs and contributing to urban vitality.

The renovation of Grand Central Terminal is a testament to the power of historic preservation combined with innovative urban planning. It symbolizes New York City's dedication to its architectural heritage and ability to adapt and thrive amid changing times.

The story of Grand Central Terminal, from its initial construction to the fight against its demolition, highlights a critical chapter in the history of urban preservation in the United States. The successful battle to save Grand Central was more than just a campaign to protect a building; it was a significant moment for historic preservation nationwide. The Supreme Court ruling in favor of Grand Central set a legal precedent that has since shielded numerous historic sites across the country. This case underscored the importance of our architectural and cultural heritage, showing that such places have value beyond their immediate utility. Elizabeth's experience of Grand Central's beauty and atmosphere is a testament to the station's lasting impact as a transport hub and a cherished public space. Grand Central's preservation victory is a powerful example of how determined advocacy and legal protection can ensure that important historical sites continue enriching our cities and lives.